"Insidious": The ACLU's Chase Strangio Slams The New York Times In Leaked Audio

In some of his first comments since U.S. v Skrmetti came down, Mr. Strangio never acknowledged or responded to the sharp critiques in a recent Times investigation of his own rhetoric and actions.

[Note: There’s a bug in this Substack which is preventing restacks if you’re using a web browser. If you’re looking to restack it, you can successfuly do so via the app on the phone. Or copy and paste the link into Notes. Thanks for doing so! —Ben]

ACLU litigator Chase Strangio on Saturday issued full-throated criticism of The New York Times’ coverage of transgender issues, calling it “insidious” and “absolutely terrible.” Mr. Strangio, who is a trans man, said that the paper is led by “this idea that they can situate us as a people to be hated.”

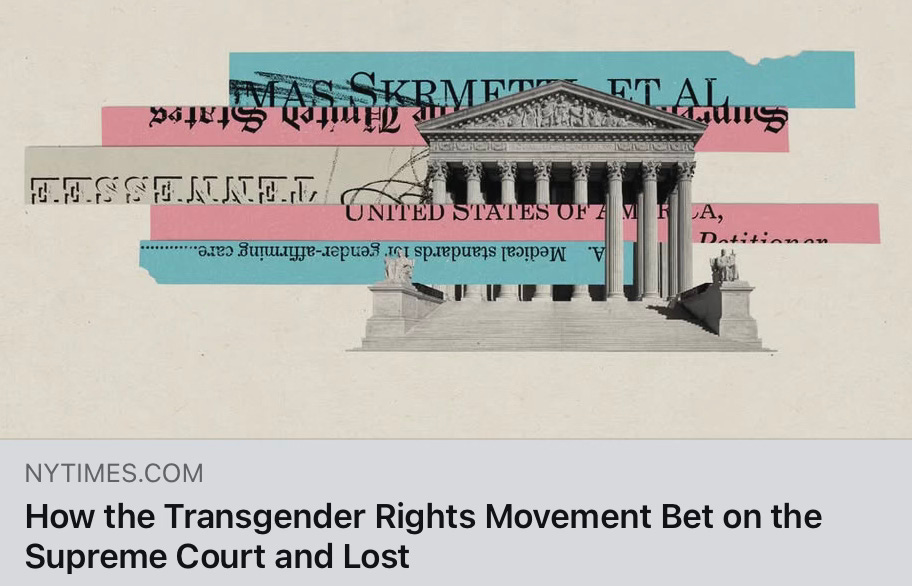

These unsparing remarks, which Mr. Strangio made during an hour-long discussion with him held at an event space in the LGBT resort town of Provincetown, Mass., came three days after the Supreme Court issued a landmark decision, U.S. v Skrmetti, upholding Tennessee’s ban on pediatric gender-transition treatment. Mr. Strangio had made history as the first openly trans person to argue a case before the Supreme Court during oral arguments for Skrmetti in December.

Mr. Strangio pulled no punches throughout the discussion, which included his first lengthy remarks since the Skrmetti decision. I obtained a leaked recording of the Q&A.

“Skrmetti is a horrible decision, and it makes no sense,” he said.

He later grimly quipped that President Donald Trump’s inauguration was “a coronation.”

These remarks also came in the immediate wake of the Times publishing a lengthy investigation by Nicholas Confessore that was critical of the ACLU, and of Mr. Strangio in particular, for pushing the Supreme Court to expand constitutional protections for transgender people based on medical practices—prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors with gender dysphoria—that are supported by weak and uncertain scientific evidence.

I’ve posted the recording of Mr. Strangio’s Provincetown Q&A below. I have also posted the full transcript at the end of this Substack. Note that the person posing the questions to Mr. Strangio in the recording is Celeste Lecense, cofounder of The Trevor Project, the LGBTQ suicide prevention nonprofit. (The volume in the straight-audio version was rather low, so I also posted the audio as a video, which has better sound quality.)

The Times article portrayed Mr. Strangio as inflexibly devoted to activist pursuits that may have alienated the public and fed the right-wing backlash during the years-long lead-up to Skrmetti. During the conversation in Provincetown on Saturday, Mr. Strangio did not acknowledge any of the Times’ scrutiny of his own actions or rhetoric. Instead, Mr. Strangio heaped criticism on Times, which he portrayed as having waged a campaign to stir up a moral panic over a tiny number of children receiving gender-transition treatments and as ultimately responsible for the Skrmetti decision.

Mr. Strangio lays into The New York Times

“I think when it comes to the trans coverage is, it’s so insidious,” Mr. Strangio said of the Times. “The New York Times, especially has been fixated on casting the medical care as being of an insufficient quality.” He said that “the characterization of the science” backing pediatric gender medicine in the Times “is wrong.”

Speaking to the legal arguments in the Skrmetti case, he said that “even accepting that there is a debate over the medical care, this isn't a quality-based argument. What the states have to show is that there's a reason why they’re treating this care differently. So even if there are different views about the best care, even if there is evidence that is not as robust as, you know, as we would like, that is true in many other aspects of pediatrics.”

Mr. Strangio faulted the Times, in particular, for what he characterized as its deferential reporting of the British Cass Review, which was authored by renowned pediatrician Dr. Hilary Cass and published last year. The review found that the field of pediatric gender medicine was based on “remarkably weak evidence.” Despite the fact that the National Health Service tapped Dr. Cass for the job because she was not involved in treating transgender youth and therefore came to the subject without a professional conflict of interest, Mr. Strangio lambasted her for that lack of experience.

He asserted that U.S. medical associations had “looked at the same evidence that Hilary Cass looked at” and concluded “that this is a robust body of evidence when it comes to pediatric medical care.”

With the exception, in part, of the Endocrine Society, this suggestion that U.S. medical societies examined the relevant scientific evidence in a similar way to Dr. Cass is, however, wholly false. The Cass Review was based in part on a half-dozen systematic literature reviews—the gold-standard of scientific evidence—of the evidence, which concluded that the science was wanting and uncertain. Major medical societies such as American Medical Association or the American Academy of Pediatrics that have been out front backing pediatric gender medicine have conducted no such reviews. The AAP claimed in August 2023 that it was going to commission a review, but there is yet no evidence that they have even started. The Endocrine Society’s current treatment guidelines did rely on two systematic reviews, but they only concerned two specific health risks and did not examine the potential benefits of treatment.

Mr. Strangio argued that the Times was planting in readers’ heads unfounded worries about, for example, fairness in girls’ sports should trans girls be included, or, “Are kids getting health care too soon?”—meaning the question of whether minors receiving puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones too young.

“And these questions have been planted in people’s minds for a reason,” Mr. Strangio said of what he believed to be the Times’ intentions, “to sow this sense that there’s a problem and a problem to be solved. And the solution they’re providing is legitimizing anti-trans laws.”

“The New York Times was terrible in covering AIDS, and terrible in covering marriage equality, terrible the immigration raids right now,” Mr. Strangio said. “It’s an institution that is obsessed with showing its own—I don't know what. Sort of appealing to the idea of both-sides approach to journalism.”

Asked what news outlets people should trust, Mr. Strangio had trouble answering the question, but ultimately named Democracy Now. He otherwise agreed with the suggestion that social media, including Instagram, was a good source of first-person information about the experience of transgender people that could stand in the place of reporting from the Times. And he alluded to LGBTQ nonprofits as other good sources.

This is a good moment to take note that in 2023, the LGBTQ media watchdog group GLAAD ran a protest truck outside of the Times’ Midtown Manhattan offices falsely claiming that the “science is settled” on pediatric gender medicine. The fact is that international debate over the science continues to evolve. Due to the findings of systematic literature reviews, five European nations have performed about-faces and begun sharply restricting minors’ access to gender-transition drugs over the past five years.

Expressing exasperation that Justice Clarence Thomas cited the Times repeatedly in his concurring opinion in Skrmetti, Mr. Strangio said that the ultra-conservative jurist was leaning on the notion, which Mr. Strangio argued was misplaced, of “this idea that” the Times is “an expert source.” He accused the Times of an ideological bias and of “providing a skewed view particularly of health care for trans people.”

Mr. Strangio said of the Times: “I think it’s more that collectively they’re like, they say, ‘We'll do this type of trans coverage to balance out the rest of the things that we’re accused of being too far to the left.’ I think it's absolutely terrible. I think their coverage has contributed more to the anti-trans laws than almost any other thing in this country.”

Lambasting the social-contagion theory

Mr. Strangio criticized the common argument that social contagion is driving trans identification in young people. This is a hotly debated notion, tightly intertwined with the wildly controversial theoretical phenomenon of rapid-onset gender dysphoria, or ROGD. Transgender advocates and researchers in the field have stopped at nothing to dismiss the social-contagion theory and ROGD as fantastical and wholly false.

However, at the recent American Psychiatric Association annual conference, leading pediatric-gender-transition psychiatrist Dr. Scott Leibowitz acknowledged the possibility that some youth—“kids who are vulnerable, searching for identity”—begin to identify as trans because they are drawn to a sense of community they might find among trans people.

Controversial Gender Researchers Launch Long-Term Study of Gender Dysphoric Youth and Their Parents

The rhetoric behind bans of pediatric gender medicine, Mr. Strangio said, “is that you are undeserving of medical care, that your identity as a product of social contagion and not the core of who you are.”

Mr. Strangio said he found it ridiculous that many people point to the fact that trans youth have other trans friends as evidence of a social contagion. “When that is just the most obvious, smart thing to do”—to seek out like-minded peers,” he said.

Bans of pediatric gender medicine, he said, were “all part of a retrenchment around gender more broadly that we’re seeing across the country.” He argued that “the rise of authoritarian governments coincides with retrenchment around gender and control over people’s bodies, people’s family structures.”

Societal anxieties about transgender identification in children, Mr. Strangio said, is based on the fear of the freedom of shattering the gender binary, a structure in which people tend to find comfort.

“The right fears gender-affirming care not because they know it doesn’t work, but because they know it does.”

“And one of my colleagues often says that the right fears gender-affirming care not because they know it doesn’t work, but because they know it does,” Mr. Strangio said. “And they don’t want people to live these embodied, full lives.”

He made no mention of widely voiced concerns of potential negative impacts of gender-transition treatment on minors, in particular a loss of fertility, as well as the potential for regretting irreversible treatments or surgeries.

Instead, Mr. Strangio continued: “We know that this care is a lifeline. It allows so many people to thrive.”

Mr. Strangio’s wording in that claim is notable, because he didn’t quite assert that pediatric gender-transition treatment is “life-saving” as many advocates do, absent scientific evidence to back the claim. In a memorable exchange during oral arguments for Skrmetti with Justice Samuel Alito in December, Mr. Strangio said that “there is no evidence in some — in the studies that this treatment reduces completed suicide. And the reason for that is completed suicide, thankfully and admittedly, is rare.”

So it is unclear whether Mr. Strangio on Saturday was contradicting his own previous admission by characterizing the treatment as “a lifeline.”

Dismissing damning WPATH records as “cherry picked”

Steve Marshall, the Alabama attorney general, subpoenaed a trove of records from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, or WPATH, as part of his defense in the case against that state’s ban of pediatric gender-transition treatment. WPATH is an activist-medical association that issues the so-called Standards of Care trans-care guidelines that are widely followed in the United States. The Standards of Care 8, or SoC 8, were published in Sept. 2022.

The subpoenaed records, which began to be unsealed a year ago, embarrassed WPATH by demonstrating that its leadership knew that the evidence behind pediatric gender medicine was weak and that they sought to paper this over. In particular, WPATH leadership suppressed the publication of at least one systematic literature review it had commissioned about trans care from evidence-based medicine experts at Johns Hopkins after WPATH didn’t care for the findings.

In his conversation in Provincetown, Mr. Strangio sought to dismiss the damning story these records told, which was compiled in a scathing amicus brief Mr. Marshall submitted to the Supreme Court for Skrmetti. The ACLU litigator said, “I think it’s this cherry picking, this microscope on our care that is not expanded to other contexts.” Referring to the effort to smear WPATH by Mr. Marshall’s team, he asserted that “they pick up random emails from doctors talking about, ‘How do we articulate the science in this way or that?’”

Mr. Strangio characterized it as bizarre that the public should spend so much energy scrutinizing the medical guidelines of pediatric gender medicine, arguing that this field had been unfairly exceptionalized with impossibly high standards that are not placed on other medical practices.

“I don’t know anything about how medical guidelines are established.”

“The general public doesn't know anything” about medical guideline development, Mr. Strangio said. “I don’t know anything about how medical guidelines are established.”

Mr. Strangio further said: “The idea that you could even rush in the United States access to medical care that requires a specialist, you have to stop knowing everything about health care. Like, that's a ridiculous proposition.” Mr. Strangio said that arguments are being propogated “by the media machine” that “there’s no oversight” and that children are being rushed onto blockers and hormones.

However, this argument conflates the time it takes to see a gender-medicine specialist with the time that a psychologist or other care provider spends assessing that child to determine whether they are a good candidate for gender-transition treatment.

As I reported in the fall for The New York Sun, it has been Boston Children Hospital’s policy since 2018 to provide children seeking blockers or hormones with only a single, two-hour appointment with a psychologist before the clinic decides whether to refer them to endocrinology.

Dr. Johanna Olson-Kennedy, who is perhaps the leading pediatric gender medicine doctor in the nation, has advocated strongly against the psychosocial assessments that WPATH advises for adolescents with gender dysphoria in Soc 8. In December, she was sued by a young detransitioner to whom Dr. Olson-Kennedy prescribed puberty blockers on the first appointment when the girl was 12 years old, without conducting a psychosocial assessment.

Mr. Strangio also neglected to acknowledge that the WPATH records obtained by the Alabama attorney general expose WPATH as having orchestrated with Mr. Strangio himself to craft the SoC 8 in a way that would help transgender advocates win in court cases. While Mr. Strangio on Saturday dismissed any exchanges revealed in these emails as unexceptional chatter among guidelines committee members, it remains a fact that these WPATH leaders, absent scientific research supporting such wording, added the term “medically necessary” to the SoC 8 to characterize pediatric gender-transition treatment. They did so for the purpose of securing insurance coverage and aiding in litigation efforts.

Mr. Strangio referred to an amicus brief submitted for Skrmetti, arguing on behalf of the plaintiffs, from a team of clinical-practice-guideline experts at Johns Hopkins, Stanford and elsewhere. He said that this group’s conclusion was “that if you cherry pick by looking at private email conversations at any medical association and use that to create a sense that this is, you know, not good science, you could same say that about anything. You always have doctors who are debating.”

That particular amicus brief, however, makes a notably false claim that WPATH engaged in a process of establishing consensus among the SoC 8’s authors known as Delphi, which the brief defines as “achieving at least 75 percent agreement on its included recommendations.”

In fact, as the documents subpoenaed in the Alabama case—the very internal emails that the brief’s authors dismiss as mere cherry picking and therefore unreliable—show that the SoC 8 authors most certainly did not engage in the Delphi process for one crucial point. At the 11th hour before the guidelines’ publication in September 2022, WPATH leadership caved to outside pressure—the pressure came from Assistant Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Admiral Rachel Levine and the AAP—and removed all age restrictions on pediatric gender-transition treatment and almost all such restrictions on gender-surgeries. The WPATH leadership did not engage in Delphi when removing these age limits.

And then, as the subpoenaed WPATH emails show, Dr. Marci Bowers, who at the time was the president of the organization, arranged for her colleagues to establish a false cover story to present to the public about why they removed the age limits. The Alabama documents exposed Dr. Bowers as having deceived Reuters about this point in the SoC 8 development process.

And yet the amicus brief favored by Mr. Strangio characterizes WPATH’s guideline-development process as having been “transparent” and “rigorous.”

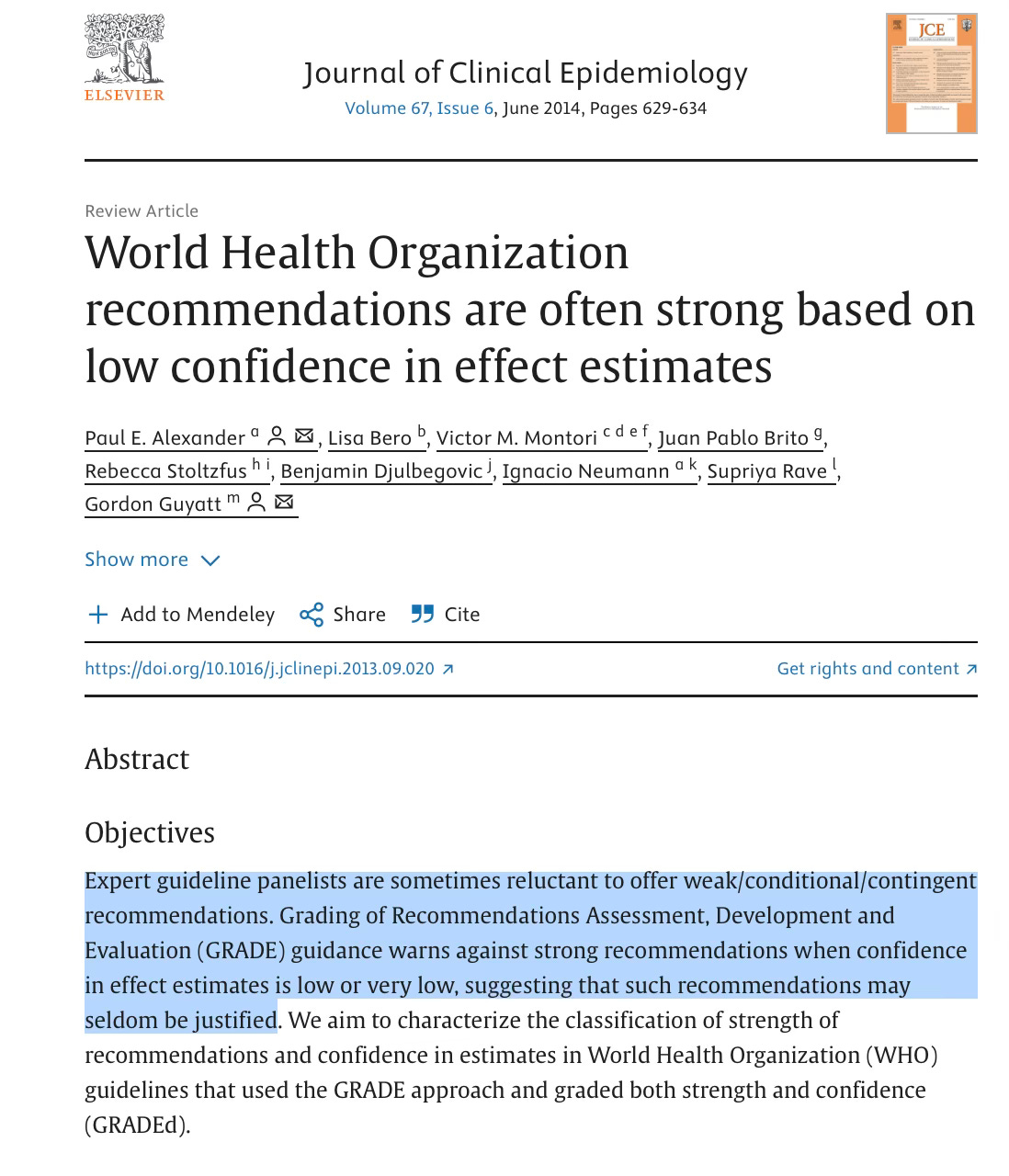

This amicus brief backs WPATH for having provided strong recommendations for pediatric gender-transition treatment despite “low quality” evidence under the evidence-based medicine scoring system known as GRADE. The brief states: “In many clinical domains, including pediatrics, there is little or no high-quality evidence. It is well established that clinical practice guidelines can make strong treatment recommendations based on so-called ‘low quality’ evidence.” (Italics mine.)

The citation for that claim is a 2014 paper by, among others, Gordon Guyatt, of McMaster University in Canada, who is considered the godfather of evidence-based medicine. A read of that paper, however, makes clear that the amicus brief’s authors are making creative use of the word “can”. Guyatt and his colleagues assert that guidelines certainly do make strong recommendations based on low-quality evidence, but they criticize the practice, stating: “[GRADE] guidance warns against strong recommendations when confidence in effect estimates is low or very low, suggesting that such recommendations may seldom be justified.” (Italics mine.)

Criticizing the Skrmetti decision

“Skrmetti is a horrible decision, and it makes no sense,” Mr. Strangio said at the Provincetown Q&A. “The whole decision is crazy…The court’s precedents really don’t allow for that contorted, just disingenuous decision. That said, I’m very used to distorted, disingenuous decisions from this court. So that doesn’t necessarily surprise me.”

In the wake of considerable chatter about Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s apparent leftward drift in her recent decisions, Mr. Strangio said he had harbored some hope that the jurist, appointed by Mr. Trump, might have voted on the Biden administration’s side in Skrmetti and overturned the Tennessee ban on pediatric gender-transition treatment. But it was not to be. “And so she ended up writing a concurrence that is much further to the right than the majority opinion from the chief justice,” Mr. Strangio said.

Justice Barrett, indeed, asserted a claim that Chief Justice John Roberts avoided addressing in his majority opinion. She stated explicitly that transgender people did not qualify for a protected-class status. Among her reasons were that detransitioning can happen, which indicates that transgender identity is not immutable—a criterion for designating a group, such as women or Black people, as part of a protected class.

“I think we’ll see some nastiness from [Barrett] and Alito still to come.”

“People will see more from her this term, still, unfortunately, targeting our community because of another case coming down about a Maryland school district’s teaching of LGBT books in elementary school,” Mr. Strangio said of Justice Barrett. “So I think we’ll see some nastiness from her and Alito still to come.”

In general, Mr. Strangio warned trans advocates against the trap of lending too much weight to major Supreme Court decisions, whether they be successes or defeats. During the early 2010s, he said, “we got intoxicated by the idea of victory in reports,” given numerous LGBTQ-related victories, including those that legalized same-sex marriage.

“If you get intoxicated by what seems like a transformational win and don’t do the work to stabilize it and build up on the infrastructure, then ultimately we’re just going to be subjected to the backlash that we’re not prepared for,” he said.

Mr. Strangio recalled that even in the wake of defeat, such as in the 1986 case Bowers v. Hardwick that upheld sodomy statutes, the ACLU began winning key cases on behalf of gay rights.

Expressing his relief hat Skrmetti was actually a quite narrow decision, Mr. Strangio said, “And when we lose a case, and we don’t lose it as badly as we might have, then that too is a victory.”

What’s next for litigation over trans rights?

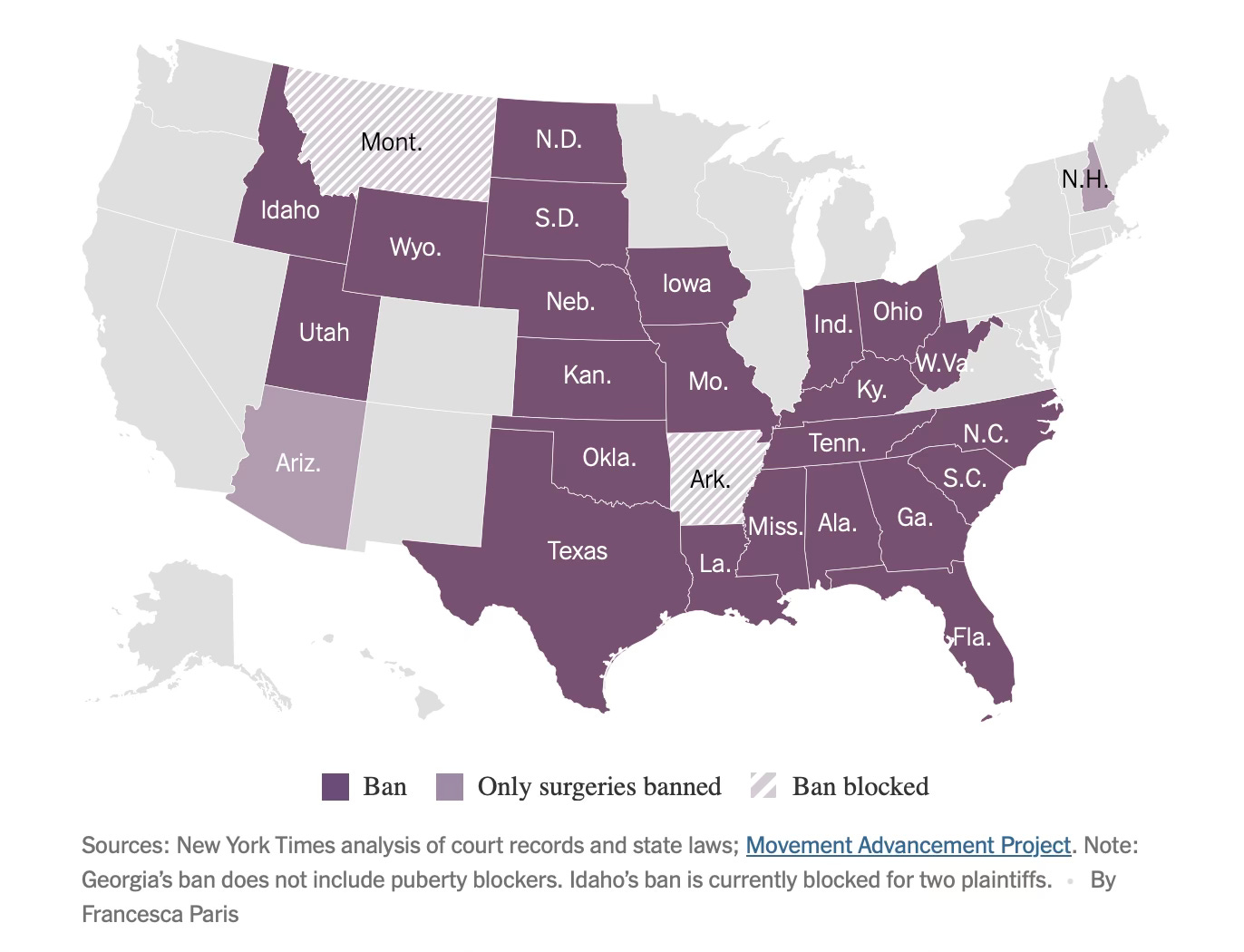

Mr. Strangio said that the state bans on pediatric gender-transition treatment will remain in effect in about 20 U.S. states, and a few other bans that have been blocked by lower courts will go live. The exception is Montana, where the state’s supreme court ruled that the ban violated the state constitution; that ban will remain blocked.

In the wake of the Skrmetti decision, Mr. Strangio said that “as devastating as this decision was and as painful as it is to see people have to continue to live under these laws” the Supreme Court ruling still “allows us a lot of tools to keep fighting and so I’m holding onto those.” He made reference to fighting against efforts to limit access to gender-transition treatment for minors in the lower courts based on theories outside of equal-protection claims—in particular due-process claims regarding parents’ rights to make medical decisions on behalf of their children. He said there were precedents in the 4th and 9th Circuit Courts that litigators could look to in an effort to fight state bans.

Mr. Strangio called on trans advocates to combat the budget reconciliation bill currently before the Senate, given its provisions to eliminate Medicaid coverage for transgender minors and adults alike.

As for the question of whether legislatures would seek to ban adults from accessing cross-sex hormones, Mr. Strangio said of Skrmetti: “I certainly think that the opinions—their logical conclusions—could be used to justify action by the governments to start to infringe.”

Addressing the question of how the ACLU would fight such a ban, he said: “I think that it’s hard to figure out exactly how we would argue that that a ban on care for adults is sex discrimination under the logic of their opinion [in Skrmetti], but we will. I think the main way we can argue against an adult ban is that saying a ban on care for adults is a form of anti-transgender discrimination.”

He also warned of mounting efforts to criminalize providers for prescribing gender-transition treatment to minors. But he said that the federal government had a limited number of criminal statutes at their disposal for such efforts, in particular if the Justice Department were to target families.

Mr. Strangio was clear that Justice Roberts’ decision in Skrmetti still acknowledged the existence of trans people. “I’m not ready to say the court has foreclosed trans discrimination claims or deny trans existence,” Mr. Strangio said. “Even though practically speaking, of course, that’s what it feels like.”

The full transcript of the June 21 Q&A with Chase Strangio in Provincetown

Celeste Lecense: I just want to start by asking, how are you?

Chase Strangio: Well, I’m very happy to be here. I was like, you know what I need is to go to a gay town. That would make this week a lot better. I have a history of being here. I grew up outside of Boston and I think when I think about this week, when I think about the decision, I think about history, queer legacies and how we build together. And what better place to come than P-Town [Provincetown] to remind myself of that as we move through this moment when so many people in our communities are under such sustained assault. And so being here is what’s making me feel good in this moment.

And as someone who does know a lot about the Supreme Court, I also know exactly what to expect from them in many ways. And as devastating as this decision was and as painful as it is to see people have to continue to live under these laws, I also know that we got a decision that disappointing it was, allows us a lot of tools to keep fighting and so I’m holding onto those.

In the decision, was there something that really surprised you? Like that you went like, “That’s crazy”?

Well, the whole decision is crazy. But as Justice Sotomayor said in the dissent, you have to contort precedence and logic to say that ending medical care, because it allows someone to live consistent with their sex, is not about sex. And the court’s precedents really don't allow for that contorted, just disingenuous decision. That said, I’m very used to distorted, disingenuous decisions from this court. So that doesn’t necessarily surprise me.

I think in this moment when a lot of people are looking for some middle ground in this court and trying to find people within the nine who might be moderate, there has been a lot of talk about Justice Barrett. And I think I even though it intellectually, I think that would been impossible to know given everything I know about her, I really also sort of bonded to the idea that she might be a vote in our favor. And so she ended up writing a concurrence that is much further to the right than the majority opinion from the chief justice, and joined Alito and Thomas in this very extreme set of views about the Constitution’s protection of trans people. So I think that was just a little bit of a wake-up call. People will see more from her this term, still, unfortunately, targeting our community because of another case coming down about a Maryland school district’s teaching of LGBT books in elementary school. So I think we'll see some nastiness from her and Alito still to come.

And does this mean that…the other 24 states—that it just paves the way for them to do what they’re going to do? The 24 states that have banned gender-affirming health care?

Yeah, so, in a sense, what’s really a devastating and important understand is that those 24 states, for the most part, were banning the health care—those bans were in effect. Tennessee’s ban was in effect. People already have lost health care in their home state. The Williams family in Tennessee, in 2023, the ban went into effect. They since that time have gone to four different states to get access to medical care for their daughter. And that’s what’s been going on in the majority of the states that have the bans. There’s a few that have been blocked in state court, for example: Shout out to the Montana state constitution. They've been able to get substantial protections for abortion, gender-affirming care for trans people. So there are some examples, but for the most part, I think 20 of those bans have been in effect for almost two years.

And nobody can contest them now.

I think that this will be very difficult to contest the ban in those states. I think there’s a few where we might be able to base on the precedence in those circuits. One of the ways that opinion was narrower was that it did not foreclose certain constitutional arguments about discrimination based on trans status. So in the fourth circuit in the ninth circuit, there’s still a good precedence that remains on untouched by the division. So Idaho, West Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina—there are opportunities to continue litigating against the bans. But mostly I think we won’t see successful challenges in federal court under the federal Constitution, under equal protection theory.

Now, to be clear, the Supreme Court did not address the due process claims. So the claim that these laws violated parents’ rights to direct the medical care for minor children. That is before the lower courts. So we live to fight another day on that theory. And as a potential point of—a troubling point—but also a potential point of optimism, there is a case coming up to the Supreme Court from the state of Montana where the government is arguing that these parents have a right to be notified of their children’s abortions. And they’re making a parental-rights argument that is sort of the other side of the parental argument—a very conservative argument usually. So the court is going to have to grapple with whether they’re going to have a principled approach to parental rights. Given the court, I’m guessing they won’t. But it is going to be something that remains in the conversation about these bans.

You know, something that surprised me, and correct me if I'm wrong about anything, because it's possible. But what really surprised me was it seemed like they were trying to disqualify the whole idea of transgender people. Like they were trying to disqualify by saying that gender dysphoria was not a medical condition, and it did not warrant the application of the healthcare.

I wouldn't think it that far, and I think there's lots of reasons to think that that is where we're going with this court. But I think, and this is totally minor, but the court says, they make a point in the majority opinion to say transgender boys are people assigned female birth who identify as boys and transgender girls are people assigned male birth who identify as girls. So they honor the existence of trans people. Unfortunately, the analysis around our health care is also part of a long history of this court being terrible when it comes to bodily autonomy. And there's a decision from 1973, called Geduldig, in which the court said that discrimination based on pregnancy is not sex discrimination, even though only people assigned female at birth can get pregnant.

But this idea that when it comes to our bodies and the ability of the government to control and regulate and decide what is right for our bodies, the court has long deferred to the state governments and the federal government. So it discounting of trans experience, but it is not unique to trans experience when it comes to this court’s precedence. And so, I would not—I mean, there’s lots of reason to be very concerned about what this court thinks about everything that I personally believe in—but I don’t think I would say there’s no applying trans identity, because they especially go so far as to say, “We’re not going resolve the question of whether other forms of discrimination against trans people would be permissible.”

And the court reaffirmed this 2020 decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, holding that it is impermissible sex discrimination to discriminate against LGBT people in employment. And not only that, they leave open the question of whether that decision has broader implications outside employment.

So those are the sort of high notes of the decisions, how much they leave open. So I’m not ready to say the court has foreclosed trans discrimination claims or deny trans existence. Even though practically speaking, of course, that’s what it feels like. Certainly that’s what the [state] governments are doing and that’s their objective.

You know, I have a problem talking about this issue with people who are not of like mind. Because people seem to think it’s like a very complicated situation, and that it doesn’t affect them. Because a lot of people I know—some people I know, don’t understand the trans experience. They see it as a choice and not as something that is inevitable for that person to have to face with themselves. One of the things that I’m so curious about you personally—and I know you’re lawyer, and you’re trained in this stuff—but to go up against the Supreme Court, to actually make a case, and knowing that people don’t actually share your view of this, like, where do you have to go inside yourself to be able to do that?

Oh, that’s a good question There’s lots of different compartments. And I think that because I spent the last 13 years going to state legislatures across the country and lobbying with, you know, Republican caucuses in Texas, in South Dakota, in Tennessee, I’m very familiar with conversations around our lives and experience that have no grounding in what I think of as reality. And at same time, there has always been, there have always been pockets in the most unlikely places where I’ve been able to connect with people.

And I come from, I mean, my father is a conservative person. My brother was in the military. I even within my own family, [have] so many divergent viewpoints. And so I try to bring that sense of possibility into these experiences. And in these legislatures, there’s a lot of times you can connect with people as parents. You can connect with people on the values that they share with you. And then, of course, they go and they say the most horrific things.

So that just meant when I was going and talking to Justice Thomas and Justice Alito, it really didn't feel like anything new. The stakes were higher, but this is how this is how judges are. So I really, in the process of the preparing argument before the Supreme Court, I really only had to focus on bringing the legal arguments to the context. That didn't feel like a new emotional battle, because that battle was every day.

And the battle is really about—again, correct me if I'm wrong—but what we're talking about is 100,000 young people in those 24 states that are being denied gender-affirming healthcare. That's right?

Yeah, so 100,000 trans people [minors] live in the states. But that’s not the number actually being denied care. That’s very small. Nationally, the estimates are there 5,000 adolescents who have received puberty blockers. It’s an extraordinarily small number of people who actually receive the care. There’s an outsize idea of how often it is prescribed because of right-wing media narratives. That said, there are 100,000 trans people, trans adolescents, in these states that may or may not need access to care that are subjected to these types of laws that are harming them whether they need care or not, because the rhetoric behind the law is that you are undeserving of medical care, that your identity as a product of social contagion and not the core of who you are.

And so I think there are two things to tease out of all the numbers. One is, there are 100,000 young people who live in states with these laws, and much smaller numbers of those people actually receive this medical care.

What do you think is at the core of the objection?

You know, I think this is all part of a retrenchment around gender more broadly that we're seeing across the country. [Unintelligible] what men’s and women’s roles should be. That the rise of authoritarian governments coincides with retrenchment around gender and control over people's bodies, people’s family structures. And that’s a part of what we’re seeing in the United States and around the world.

And then when it comes to trans people, this is a manufactured set of concerns. I mean, Media Matters reported very recently that Fox News ran 400 segments on trans athletes in four months. That isn't, first of all, there are not 400 trans athletes among young people in the United States, not even close. So that means that a group of people that in some states, there’s one, maybe zero, and the people who are in the media climate are getting this manufactured sense of an emergency a crisis. And that has drastically changed the climate. You know, it was not the case five years ago that this had the level of resonance that it does now. It's a media manufactured crisis in people's minds, completely contrived.

And the purpose of it, I think, is twofold. It's much like what we saw in the early 2000s around marriage equality. The driving people out to vote in elections with this, you know, idea of a changing world. And it's effective. But now the media climate has changed so dramatically.

And then I think that there is this fear of not knowing that, you know, M. Gessen had this op-ed in The New York Times, this week in the aftermath of the decision, and I really recommend everyone read. Because it is sort of the idea that parents are afraid that they don't know their children. In the context of the pandemic, that’s when we saw this real rise of the backlash around curriculum. And all of a sudden, when kids were home in school were closed, it sort of showed parents: “Wait, what is happening? What is this world? I don't like this changing world. I don't like this idea that maybe I don’t know myself and I don’t know my child.

And I think that's part of it. This anxiety, and when people are fearful, they sometimes [resort to] these mechanisms of control, and controlling what can be true for people and making our ideas of possibilities smaller is a, I think, unhealthy way to respond to that. But I think we we're in an unhealthy society, and that it is a part of what's going on here.

You know, it's interesting, you bring up the pandemic, I had an incredible experience during the pandemic and a unique one, which is I started the Future Perfect Project maybe two years, two and a half years before the pandemic started. And we traveled around the United States going into schools and LGBT centers and offering workshops and we’d stay for a week with young people and work with the queer young people in high school and really get them to tell their stories, make music with them, really just encourage them to speak their truth. Because I was fascinated by what was happening in 2017, ‘16, ’17 and ’18. And then the pandemic hit, and we instantly moved everything online, all of our workshops. And suddenly there were hundreds of young people from their bedrooms, zooming in, doing these workshops, and changing their names and their pronouns.

And I would say from my personal experience, it was the most incredible experience of watching a metamorphosis happen. It was like watching butterflies come out of their cocoon. And if there's a contagion that people are, it seems to me that they're afraid of, it's the contagion of happiness, that these young people actually, the freedom to express themselves and to be themselves is a terror. And as was my joy, as a young, queer kid, to my parents who did not know what this was. They knew what it was. They just didn't want it.

And I think to myself, we're just in another inflection point with this. And I'm so excited to be able to share what they make, because they're the best advocates for themselves than anybody else could possibly be.

But what I find is that people diminish their happiness and that they diminish their agency and they diminish the things that they have to say by saying, “It could change." And I'm like, the irony is they changed me. I changed my name, I changed my pronouns, I was like, “Wait, I thought I was a gay man for like, my whole life.” And I was like, “I never felt that.” I mean, I enjoyed sex. But you know, I realized I was non-binary. And they encouraged me. And I think partly why adults are afraid is that they're going to have to change as well. Right? That they're going to have to ask themselves some serious questions about their own identity.

Yeah, I think of the things that I always say is the fear of transness is the fear that people have of freedom. There is something that—constraint is comforting. If there's only two binary sexes to have—it's the same reason why queerness makes people afraid. It's fact that I am supposed to, there's men and women who are attracted to each other, and that's all that's available. If you expand that, then people do have to ask questions of themselves, and they have to be confronted with people who are at a very young age, wholly comfortable with this idea that the world is bigger and more there are more possibilities. And I think that is really scary for people, and they want to shut it down. And one of my colleagues often says that, you know, the right fears gender-affirming care not because they know it doesn’t work, but because they know it does. And they don't want people to live these embodied, full lives. And they don't like the idea that there can be trans people running around and they wouldn't be able to identify it based on their own ideas that what transness is. And that's what they want to stop.

“We know that this care is a lifeline.”

And you think that the bans against and gender-affirming health care are really a way to be able, that people are forced to reveal their transness?

I think it's a combination. I mean, I think it's [that they’re] forced to reveal their transness. And I think it's just going to make it harder for people to survive. And, you know, I don't think it's hyperbolic to say so, because we know that this care is a lifeline. It allows so many people to thrive. And if you think about what it means, it's different, say, for my generation and older, when we didn't have access to it and then we got it. I mean, they're ripping it away from people who had it. We which is even more dangerous.

And cruel.

And cruel. And they know that it’s cruel, they see that it’s cruel. The decision came down the same day that the Trump administration shut down the hotline LGBTQ youth. It's a systematic, across-the-board way to use every branch of government to limit survival opportunities. And the LGBT community is on the only community that has experienced this in this history. I mean, we’ve been balancing Black people and indigenous people and immigrants. I mean, look at what we're doing right now. We're diminishing survival opportunity for people by fear and by cutting off resources.

With people I find are going are really under-educated about the [gender-affirming treatment] protocol. They don't really understand it. They don't understand the steps that have been worked out to be able to allow this on-ramping to become trans.

Yeah, they don't understand. But it's also the case, but it's like, you don't understand anyone's medical care or protocol.You know, don't, it's not like you're like sitting there being like, oh, like, are those parents really looking into the, you know, Greek guy that invented Ozempic? Like, we actually don't pay attention to other people’s in medical care and why should we? And why do you care about someone else's marriage? It doesn't concern you. And so, if anyone believes that outsize fixation on how one group of people operates, it's so out of the bound of how we actually exist in the world.

The idea that you could even rush in the United States access to medical care that requires a specialist, you have to stop knowing everything about health care. Like, that's a ridiculous proposition. I mean, if you want access for your child, and they're like, “Oh, in 2027 we have an appointment.” And so it's deliberately disturbing that people are deliberately like letting go of their critical faculties to make these arguments. But it is true, of course, they're also to be told by the media machine that kids are being rushed into care. That there's no oversight and they're getting hormones with the pharmacy, without their parents. That of course, is not true.

And speaking of the media, I'm disappointed, fascinated, outraged, by the stance of The New York Times, and their coverage of trans lives. It's just out of step with what we know. And it's based on all sorts of faulty information.

Yeah, it is. And I, too, I'm very frustrated. It's also the case that The New Times was terrible in covering AIDS, and terrible in covering marriage equality, terrible the immigration raids right now. It's an institution that is obsessed with showing its own—I don't know what. Sort of appealing to the idea of both-sides approach to journalism

“I think [the New York Times’] coverage has contributed more to the anti-trans laws than almost any other thing in this country.”

Have they asked you to write an op-ed?

I have written twice. I think it's more that collectively they're like, they say, “We'll do this type of trans coverage to balance out the rest of the things that we're accused of being too far to the left.” I think it's absolutely terrible. I think their coverage has contributed more to the anti-trans laws than almost any other thing in this country.

It's, you know, Justice Thomas' concurrence cites The New York Times, I think, 10 times. [The correct number is seven.] It's very, very often that the briefs the state governments reference New York Times articles, which is in and of itself, a bizarre thing to do. We have evidence in these cases, we have factual records, we have doctors putting in testimony in cases where we’ve gone to trial, when there’s been fact finding, which is the way the law is supposed to work. They still go to the New York Times. It's this idea that it's an expert source when it's very much not an ideological source and it's providing a skewed view particularly of health care for trans people, but the coverage goes back you know, for decades. [Unintelligible] this orientation. And this idea that they can situate us as a people to be hated. And that has been that has been true for it for a long time.

I think when it comes to the trans coverage is, it's so insidious, and the challenge is that so many people don't have any counter-narrative, don't have other sources of information. And that's why they get caught up in this world. This idea: “Are kids getting health care too soon?” “My daughter plays sports…” And these questions have been planted in people's minds for a reason, to sow this sense that there's a problem and a problem to be solved. And the solution they're providing is legitimizing anti-trans laws.

And where do you think people should turn to for more accurate information?

You know, I mean, I think that's a hard question, because I think we sort of curate our own information on different topics and sort of find the sources that we trust and rely on. And I don't have a good answer to where you should get all of your news from. What do you think?

Democracy Now.

Democracy Now.

Yeah, very helpful. You know, really Instagram is very helpful in terms of hearing from people directly—like you, by following people like you and hearing from you directly.

Yeah, I think finding the people that you really trust is so important. And I think that organizations that provide information on their social media pages as well.

You know, I asked this young person that we work with. They're now, when I first met June, she was 18 years old. And she was in a workshop. And she said the most beautiful thing. And I think maybe I'm going to quote her if I can. It sort of feeds into this question: I read this thing that you said that we have to reinvent what's success looks like. And I was wondering if maybe you could talk a little bit about.

So one of the things that in my mind happened between 2011 and 2015 as we started to have a lot of legal successes—from striking down the Defense of Marriage Act, to the winning of Obergefell, having state level wins on behalf of LBG people, but also LGBT people. We got intoxicated by the idea of victory in reports. And the problem with victory in the court is that it is just necessarily limited. And if you look at 1954, the court decides Brown v Board of Education, and you look at 2025 and we still have a racial segregation in schools. They just use different ways to do it: housing policies, they use class lines. And the problem was an over-reliance on law. If you look at something like Roe v. Wade—same thing. It’s a huge success in the courts with decades of backlash.

“If you get intoxicated by what seems like a transformational [court] win and don't do the work to stabilize it and build up on the infrastructure, then ultimately we're just going to be subjected to the backlash that we're not prepared for.”

And so victory isn't always going to be a court victory, especially a Supreme Court victory. And if we look at Bowers v Hardwick in 1986, it was a loss, a categorical devastating loss. The Supreme Court said that states can criminalize same-sex intimacy. Sets back legal advocacy for decades, until the court overturns it in 2003 with Lawrence [v. Texas]. But within that moment, there were lots of victories. There, the ACLU’s LBGT Project was founded within months of Bowers v. Hardwick. We started to win local cases on behalf of individuals to make sure they weren't evicted from their housing.And there are victories every day where people, you know, stop a community member from being deported, where you show up and help someone move from one state to another to get health care and know, we shouldn't have to only rely on each other. I believe that the government should take care of us. But we have a capacity to make our own successful interventions in this moment. And when we lose a case, and we don't lose it as badly as we might have, then that too is a victory. That too leaves us avenues to keep fighting. And there's all sorts of examples of that. And there's all sorts of wins we’re having in the lower courts right now in a range of issues in litigation against Trump that seemingly were foreclosed by other terrible Supreme Court precedence. Whether it was the immunity decision, or the affirmative action decision, or Dobbs—all of these catastrophic losses have made way for other wins, have left open other possibilities. And so that is success. There is not just one form of winning. If you get intoxicated by what seems like a transformational win and don't do the work to stabilize it and build up on the infrastructure, then ultimately we're just going to be subjected to the backlash that we're not prepared for.

“And every time we stop something, even for a short period of time, even if it's ultimately overturned, four months where someone gets health care they wouldn't otherwise been able to get is a win.”

You know, I was at an event where [Lamda Legal CEO] Kevin Jennings was talking, and I was amazed when he gave everybody the numbers of the cases from just last year that they'd won. Together, you all work together, I understand. And I was also surprised that the ACLU and Lambda Legal and other organizations, you have these meetings where you decide, “Okay, you take this case, you take this case.” But I was surprised that so many of them were won.

Yeah, we've won we've won so many cases, we’ve lost cases. We continue to win cases against the Trump administration. And I think one thing that is so important is, you know, Skrmetti is a horrible decision, and it makes no sense. And also, it is not going to foreclose litigation happening against the Trump administration. Much of it is grounded in different legal theories altogether. And a lot of it is based on the president's violation of the separation of powers, exceeding his constitutional authority, to infringe on the role of Congress and other theories. So that will all continue. And every time we stop something, even for a short period of time, even if it's ultimately overturned, four months where someone gets health care they wouldn't otherwise been able to get is a win. I really firmly believe that. Because the work of law is always harm reduction work. And so if we reduce those harms, that is successful in my view.

Okay, I found the quote. So June is a young person that I met in a workshop and is now trans. And I asked her recently what she thought about what was happening. And this is what she wrote me. “The U.S. government cannot be the authority in what's real and what's not. You create your realness, in your relationship with yourself and the people who see you and love you. The government didn't think Marsha P. Johnson was Marsha P. Johnson. But she did and her friends did, and we do the same today, decades after her passing. That's where her realness comes from. We will keep each other real.”

That’s amazing.

Just to give another example, I was in January, the week of the inauguration—is that's what's called? They're still calling it that.

The coronation.

And there was a 15 year old boy, his name is Lance, and it was so moving to me because he was just months away from starting this hormone replacement therapy. And he was 15 years old. And he knew that that was probably not going to happen. And he was going to change the trajectory of his life. And we were interviewing him for this podcast that we have called “I'm Feeling Queer Today.” And we asked him, "Well, do you have any message for other LGBTQ+ young people?” And he said, “Yeah, how do I say this? Anything you can think to be, or any identity you can adopt for yourself, it's probably been done before. And I'm not telling you that so that you don't feel special, I'm telling it to you so that you don't feel alone. And you'd be smart to look to your elders and study your queer history to learn how our ancestors adapted to the circumstances that are worse than the ones that we are living through.” And I thought, this is why they’re so afraid.

It's so powerful.

“I can't even believe we've legitimized this idea that people are becoming trans, through a contagion, which is evidenced by the fact that they locate peer groups online and in person.”

And in that moment, I think the thing that really shocked me so much about these young people is their ability to understand the timeline. They're the first generation to really come of age with an awareness that people have made sacrifices, that people have fought for their rights. And they also have a sense that people are coming after them and they have a responsibility to those young people in second and third grade to model for them what it looks like to be a trans person or a nonbinary person will work just queer.

And I think that's one of the reasons it’s so insidious that they've adopted that a social contagion frame. Because what it does is it encourages isolation. It suggests that the mere process of identifying yourself with your peers is somehow indication that they’re deviants—a lack of realness. That they'll say, “Oh, well, a lot of trans people have trans friends.” Yes. So the formation of peer groups is being weaponized against people. And it's the same way with trans women of color on the street, when they congregated together, were arrested for loitering or sex work. And so the way the state turns against people to keep us from forming our communities. We have to be so vigilant to that practice, because it is incredible that people are finding each other. That is so beautiful, especially for those of us that were so isolated as young people, and they're using it so consistently to justify the discrimination. And that’s one of the things I want to fight against so aggressively. Because I can't even believe we've legitimized this idea that people are becoming trans, through a contagion, which is evidenced by the fact that they locate peer groups online and in person. When that is just the most obvious, smart thing to do.

It's been their salvation, each other.

Each other.

“Lawmakers in my experience in lobbying across the country, do not care whether something's constitutional or not.”

I want to open it up to some questions from people.

Audience Question: Two questions. First of all, if this opinion appears to relate to minors, do you think it can be expanded like Roe v. Wade to adults sometime in the future? And second of all, you said that if the decision left open tools that you can use, you mentioned two—equal protection and the precedents in the circuits—were there other tools you thought could be used to fight?

So yes, the first part of the question is about whether there can be expanded to bans on care for adults. I certainly think that the opinions—their logical conclusions—could be used to justify action by the governments to start to infringe.That’s already happening. So many states have started to cut off, for example, Medicaid funding for gender-affirming care for people all ages. The budget bill has Medicaid ban, and it's currently pending before Congress. I mean, if there's one single thing that we can do nationally right now is to mobilize against the bill. The Senate version retains the Medicaid ban on care for trans people. So that will drastically affect the ability of people to access care.

Now, lawmakers in my experience in lobbying across the country, do not care whether something's constitutional or not.That's never been a compelling argument. They’ll say, “If something’s unconstitutional, so sue me.” So I think they would have done that. The question is, do we have tools to challenge these attacks on care for adults? I would say, always, let's try to stop them from passing. Which is why I think lobbying against the budget bill is so important. In terms of litigation, tools that remain in Skrmetti opinion in itself. The court is very clear to say that its decision applies only to care for minors. I think that it's hard to figure out exactly how we would argue that that a ban on care for adults is sex discrimination under the logic of their opinion, but we will. I think the main way we can argue against an adult ban is that saying a ban on care for adults is a form of anti-transgender discrimination. And the court said this wasn't that in part because it was limited to minors, it didn't reach more broadly. A lot of the attacks on care for adults are even more amenable to that theory, which has been left open and the court explicitly left it open, especially in its [unintelligible] of its logic to a ban on care for minors.

The other thing is because the court explicitly did not reach the question of whether Bostock, the Title VII case applied outside of the Title VII context, we still have statutory arguments available to us. So this was a constitutional case. There are statutory claims under the Affordable Care Act that remain for us, which have almost universally held in our favor when we bring claims under the Affordable Care Act, which uses Title IX’s education theory of sex discrimination.

“We'll take what we can get. We'll keep fighting, and hopefully we can have some success in lobbying against the attacks.”

So I think there are tools. There are statutory tools. There's constitutional theories of anti-trans discrimination. Those were all explicitly left open by the court, whereas the lower court's opinion foreclosed all of those. And so it's much narrower than what we were appealing from. We'll take what we can get. We'll keep fighting, and hopefully we can have some success in lobbying against the attacks. It's been really disheartening to try to stop things in state legislatures over the past four years when we had had a lot of successes. Obviously, corporations have stopped lobbying for us. The consistent erosions of the Voting Rights Act have been catastrophic for the composition of state legislatures.

There's another big voting rights decision to be decided by the court this term. And they're going after each section of the Voting Rights Act. And that then makes it that much harder to strike back against these highly gerrymandered legislatures. So we also have to see the ways in which these parts of government [unintelligible] not working together.

Audience Question: So getting very practical: For the states that had laws, what happens to those young people who are currently taking hormones or want to initiate hormones? What are their legal options? Do they have to move? Or is mail order an option? Does it depend on what specific state law?

It depends definitely on what specific state law. I think that because of the federal government that we have right now, I would be—they are going after mail order everything. And they're going after mifepristone, and they can use the Comstock Act. They have indicated that they want to use the anti-obscenity mail laws to get at providers. You can start to see states start to criminalize providers. So that’s an area where I think people need to be very well advised when it comes to moving medication across state lines, because we have a justice department that is just eager to prosecute people. You can see them champing at the bit.

The good thing is in terms of federal criminal statutes, there's just a smaller number of them, generally speaking, and there's not as many ways for the federal government to criminally go after providers, and even fewer ways to go after families. So I think that that what's ultimately going to happen is what's been happening, which of these families can move if they have the resources. They can travel out of state as many people do. And there are clinics that are trying to create border clinics. So state by state border. So southern Illinois has been an incredibly important place for the Midwest for access to abortion and beginning to be so for access to gender affirming care for minors. So investing in that type of clinic opening is going to be critical in Tennessee, where, you know, this case originated, care has been unavailable since 2023. And some of the abortion clinics that had been gender-affirming care providers started to open clinics in other states very close to the border, where it's funding is legal. And I think that's the practical reality. It's a lot harder with puberty blockers than it is to do with hormones. It's just been more expensive, it's harder to find providers to administer them. Whereas the adolescets 15 and older going on hormones are going to have an easier time.

Audience Question: My question is that the New York Times from this week? I think it was Nicholas Chris. Com—

Confessore, yes.

The article seemed to talk about an evidentiary predicate that we have had an impact on the majority decision that partly came out of the record in the Alabama case. And you know, the way the article described it, I'm just wondering about your response to this—is that there's been kind of pulling back in the medical unions, not only here, but in England, possibly in Denmark, but elsewhere in the world. I guess about the terms “lifesaving,” “medical necessity” that seemed to be what the article was describing as to whether the initial studies that were relied on in the movement were valid—quote, unquote. And so I don't know if the majority decision cherry picked. I don't know if the a characterized where things are. But if it's accurate that there is this kind of reassessment, I guess, that may be underway. How do you factor that into future cases, maybe using the due process clause of state statutes or the ACA or that kind of thing?

Yeah, so there's like a first important legal response, which is that when it comes to litigation, the court is supposed to confine itself to the record in the case. And so you have the record in the case, the court didn't rely on the Alabama case. They relied on whatever they wanted to rely on. And that's something we've seen a lot. So, for example, in the affirmative action case that got rid of the constitutionality of affirmative action, there was a whole trial that the court ignored. And that's been a trend in the court, where you have these factual records, and the court just decides it's going to do what it's going to do—to the real upending of legal precedent.

“I think the other thing that's important to keep in mind in these pieces [in The New York Times] is that the characterization of the science is wrong…Even accepting that there is a debate over the medical care, this isn't a quality-based argument.”

I think the other thing that's important to keep in mind in these pieces is that the characterization of the science is wrong, and I'll get to why. But the other thing is that even accepting that there is a debate over the medical care, this isn't a quality-based argument. What the states have to show is that there's a reason why they're treating this care differently. So even if there are different views about the best care, even if there is evidence that is not as robust as, you know, as we would like, that is true in many other aspects of pediatrics.

And if you compare the way these same states treated, for example, Covid treatments, ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine, which were known to be ineffective, they allowed people to make those choices. A lot of these states have what are called right to try laws that you can make decisions for yourself and your child when it comes to medication. So it's a differential treatment, that’s the legal question at issue.

And then The New York Times, especially has been fixated on casting the medical care as being of an insufficient quality.It’s been a campaign in The New York Times and elsewhere. And part of it relies on something called the Cass Review in the UK. And the Cass Review was commissioned by NHS, Hilary Cass is a pediatrician. She has no, any experience in gender-affirming medical care. But I think perhaps the most important thing about the Cass Review, this doesn't have any new evidence. These are all just different analyses of the evidence that does exist. And the medical associations in the United States, and many European authorities retained a review that looked at the same evidence that Hilary Cass looked at, that this is a robust body of evidence when it comes to pediatric medical care—plus the decades of clinical experience that we have supporting the care.

And what happened in Alabama is that in the course of the trial and in the course of litigation, the courts have allowed for an extensive discovery into various medical groups where they pick up random emails from doctors talking about how do we articulate the science in this way or that.

And again, this comes back to put microscope over under anything, you don't have anything to compare it to. The general public doesn't know anything. I don’t know anything about how, you know, medical guidelines are established. But one end of this brief, which was a friend-of-the-court brief we had before the Supreme Court in Skrmetti took on this question. It was from expert medical researchers at John Hopkins and Stanford. And what they said, is that if you cherry pick by looking at private email conversations at any medical association and use that to create a sense that this is, you know, not good science, you could same say that about anything. You always have doctors who are debating. Is this the right thing?Is this not? Is this new intervention for, you know, this care right or wrong? You’ll see this in all sorts of different types of medical interventions, including one that endocrinologists use for other purposes and using the same medications. I think it’s this cherry picking, this microscope on our care that is not expanded to other contexts. And a lot of it looks like the exact types of tests that that happens to abortion care at various points. Oh, some people regret their abortions. Actually, they're more risky than you're being told. We have whistleblowers within the clinic. We're telling you that people aren't having oversight over how the abortions are being provided. You can do that for any care. It's being done to our care for a reason.

And tens thousands of words in The New York Times have been noticed this. But, you know, there's all sorts of things that people have where if you looked at it under a microscope, you could always find dissenting things in there, you could always have more evidence. That’s the reality.

But even if everything they say is true, it wouldn't actually meet the legal standard. States do not ban medical statements by and large, except for abortion, except for this. And that should tell you something too.

Audience Question: Chase, thank you so much, for your fierce, loving care of the young people in our communities. I'm a college counselor by day. So I have a front row seat to the challenge of being queer in this country right now. And it's a tough row to hoe. My question, though, is more from the perspective of a parent. My wife and I are parents of now 23-year-old young man who is assigned male, as it turns out, appropriately at birth. If I think about being a parent now, I wonder if it would feel at some level presumptuous to assign a gender at birth. Does anybody have a kid and say, "We don't know yet”? And what would that what would that look like?

People do do that. I think there are a lot of people who do that and let their child tell them. And I think those people are, you know, doing a service to their child. I mean, I didn't do it. I, you know, I took my child’s sex assignment and went with it. But I do think there is something to be said. A lot of trans parents are doing that with their kids. And then everyone's like, “Oh, you're making your kids trans.” And I'm like, “Well, there's lots of cis people making trans kids. Lots of straight people make gay kids, turns out.” I was at this meeting of advocates from around the world, and so many of the people from the US and the UK had children. And so many other queer people from other parts of the world, were like, “Oh still haven't had the opportunity for as much queer-family formation.”

And one of the things I love about queer families is the openness to people's exploration. And I think every kid benefits from that in every way. Because we can't know who we’re ever going to be. And oftentimes our expectations that are based on our own experiences are just an impediment to their process.

Celeste Lecense: I have two friends, lesbians, who had a boy child. And they were very adamant in the beginning about not really you know, trying to see if they could navigate that space of openness. It became so clear almost immediately that this kid was definitely, like, a boy. You know, from the womb. Make no mistake. Now they're trying to dissuade him from using swords and guns. But they're fighting a good fight, and they're trying to raise a good man.

“There's lots of ways where the administrative state is antithetical to queerness and always has been.”

Audience Question: I'm curious about the legal implications. Like, what happens if you've got to choose your gender from the get go, does that have any implications for restricting care? I don't know.

I mean, I think we have to, legally, I think we're still, I think the administrative state is still assigning sex, and there's not really a way around that easily in the same way that we're so far behind, even in parental, getting, you know, same-sex parents on birth certificates, having three legal parents. I mean, there's lots of ways where the administrative state is antithetical to queerness and always has been. So I do think it's still a fight. But the realities of pushing back on bans on gender-affirming care, I think, are illuminated by that question—which is that, you have to decide that someone's sex, if you are going to decide what's inconsistent with it. And that was one of the arguments that we made in the court. Sex is the dispositive factor here. And that's why Roberts’ opinion makes no sense, and he knows it.

Audience Question: I just want to make a comment about that decades ago, I went to a grand rounds for obstetricians and pediatricians about intersex infants. And the presenter at one point said, you know, "The child is born, and if you can't immediately say male or female, it's an emergency." One of the residents asked, “Well, you know, in the majority of these conditions, there's no medical problem, the kid’s healthy. So what do you mean by emergency? Is it a psychiatric emergency for the parents? Because it's a boy or a girl? Well, we don't know yet.” And it never occurred to me to ask what they do about the birth certificates, but we have a whole history of that too, starting with John Money at Hopkins doing horrible things.

Horrible things. And that’s been used against trans people as well. Obviously, the reality of intersex individuals is a reputation of every aspect of binary sex. They often won't make what they think of as a temporary sex designation on an intersex infant. But, and this is a very small subset of intersex individuals, who at birth, there is some ambiguity of whether they have a typically male or typically female body, although percentage-wise there are a lot more intersex people who realize at puberty or later in life. And they're, after a very very long time of these portable, nonconsensual surgical interventions, which continue very much, by the way, and all of these laws that prohibit gender-affirming care from trans minors, have an exception to permit the ongoing non-consensual surgical correction, quote unquote, correction for intersex infants, under just the emergency is it upsets the binary. That’s the emergency. And that is what is being protected.

But even the endocrinologists and neurologists who will testify on how these bans, when they're cross-examined about how do you ultimately decide what is the quote-unquote proper sex for an intersex individual, they'll say based on what they tell you. So they recognize that as a you know, sort of prevailing medical reality in this one context that they wouldn't for trans people.

Celeste: I just want to mention Heightened Scrutiny. I saw it at Newfest, the premiere of a beautiful documentary about Chase and about the case, and that started how long before the case was—?

That was six months before the argument. The documentary was has the whole media critique in it as well.

I am an independent journalist, specializing in science and health care coverage. I contribute to The New York Times, The Guardian, NBC News and The New York Sun. I have also written for theWashington Post, The Atlantic and The Nation. Follow me on Twitter: @benryanwriter and Bluesky: @benryanwriter.bsky.social. Visit my website: benryan.net

Being relatively new to this topic (I've been taking a deep dive only since last fall), I didn't know much about Strangio. I'm shocked to see that such a deluded extremist ideologue was allowed to play such a leading role in the Biden administration's policy drives. No wonder people who cared about this issue were driven to vote for Trump (which I would still never have done).

This idea that the medicalization of gender nonconformity in children is a way to transcend, rather than reinforce, the gender binary is the most vexing part of Strangio's delusion. That they think this whole project is progressive is preposterous.

There is nothing progressive about denying biology. There is nothing progressive about sacrificing women's rights to men's desires. There is nothing progressive about subjecting children to experimental body modifications in order to make their bodies fit the gender stereotypes society, including people like Strangio, have put into their heads.

And most of all, there is nothing progressive in lambasting a newspaper for reporting facts, even if you disagree with them. The entire trans project is fundamentally authoritarian. It cannot exist without forcing everyone to pretend that 1+1=0. Calling any disagreement "insidious", i.e. morally despicable, is fundamentally illiberal, and Democrats are not going to get out of their electoral hole until they understand this and abandon this regressive, reality-denying ideology.

"Mr. Strangio characterized it as bizarre that the public should spend so much energy scrutinizing the medical guidelines of pediatric gender medicine, arguing that this field had been unfairly exceptionalized with impossibly high standards that are not placed on other medical practices."

What an ignorant statement. My child was diagnosed with a serious lifelong medical condition 9 years ago. There are much higher standards of care placed on diagnostic testing, drug prescription, and follow up care for her diagnosis than anything we encountered during the time she was in an extreme mental health crisis during the pandemic lockdowns and suddenly identifying as trans (now desisted 3 years). We were living in two medical specialty worlds then: neurology and psychiatry. I can assure Strangio that the standards of care and following of evidence based practice for anything related to trans or gender dysphoria were much, much lower - truly nonexistent - than with any neurologist who treated her. Strangio is showing immense ignorance with that statement. But the whole interview sounds like Strangio was somewhere between desperately making excuses and grasping at straws and throwing a tantrum.