Why Special-Interest Groups Are Motivated to Foment Fear

Such groups frequently downplay good news about their area of concern to sustain their own legitimacy. But this comes at a cost.

Some published studies detonate into a mushroom cloud. Others bloom with good news.

This year, the coming of spring brought a latter such paper.

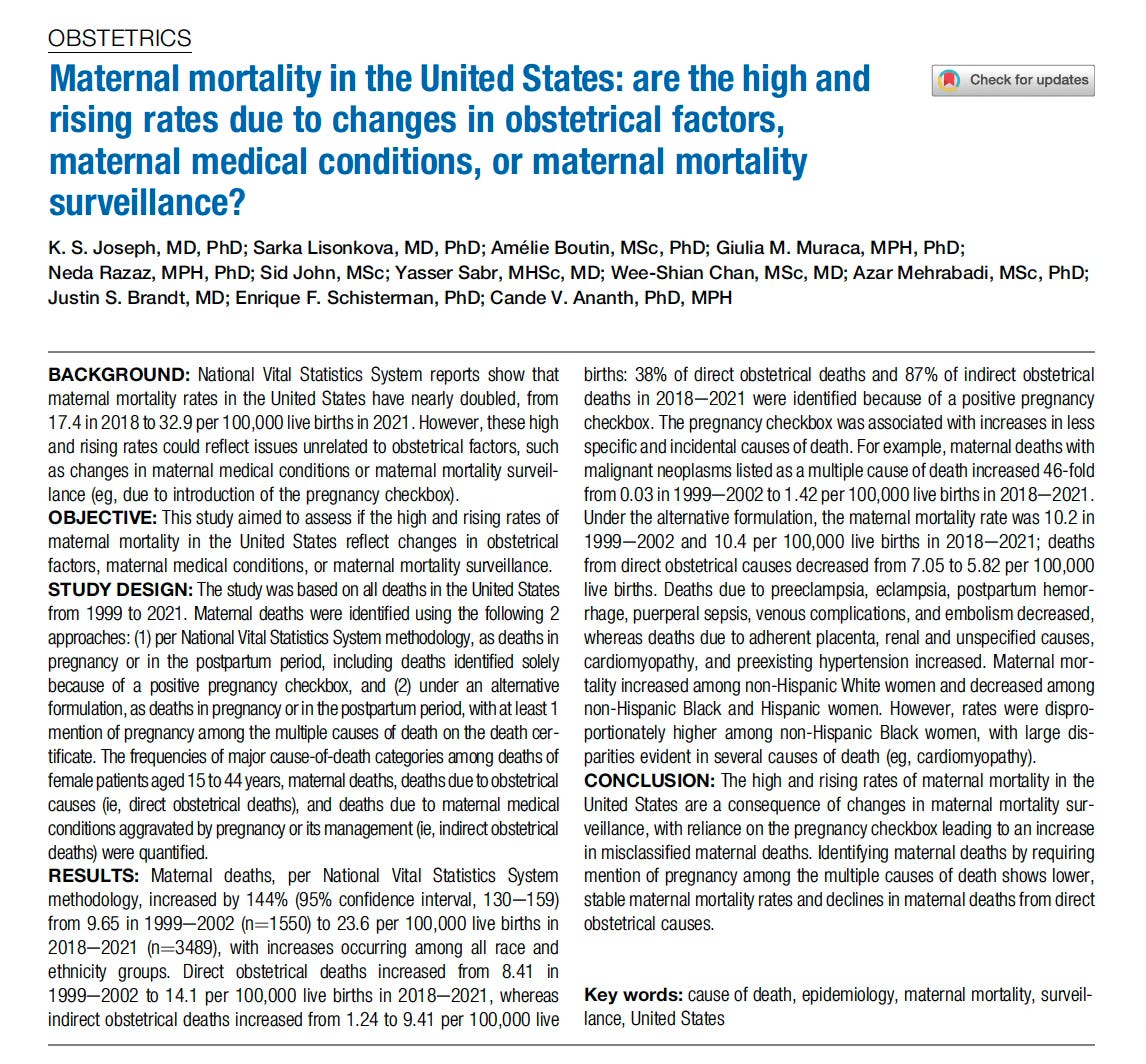

Since 1999, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistics System had charted a shocking doubling of the annual maternal mortality rate and then a sudden spike in 2021. But a new study quite hopefully suggested that the death rate has likely held stable throughout the 21st century and remains on par with rates in the U.K. and Canada.

The apparent egregious miscount, the investigators asserted, was the result of faulty CDC surveillance practices that relied on a checkbox denoting recent pregnancy, which was added to death certificates in 2003. Thereafter, nearly all deaths among women categorized as recently pregnant were counted as maternal mortalities, inflating the total with deaths unrelated to pregnancy.

And so, with the publishing of this paper, on March 12 in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the U.S. maternal mortality crisis that had been such a source of dire concern turned out likely to have been overblown.

Good news, right?

Wrong, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The medical society swiftly issued a sharply worded press release that — while refraining from directly disputing the revised estimate — criticized the study for neglecting to mention areas of ongoing concern, including persistent racial disparities (which the paper concluded have likely narrowed) as well as maternal deaths that occur beyond the 42-day postpartum period.

“To reduce the U.S. maternal mortality crisis to an ‘overestimation’ is irresponsible,” ACOG scolded the study authors, “and minimizes the many lives lost.”

Considering the new paper offered reassuring statistics about one of ACOG’s key patient populations, the organization’s rebuke was remarkable to K.S. Joseph, an investigator at B.C. Children’s Hospital in Vancouver and the study’s lead author.

“Many people were shocked by that negative reaction,” he said of recent conversations with OB/GYNs.

They probably shouldn’t have been. ACOG’s damning response speaks to a common dynamic that often unfolds when new evidence challenges the animating narrative of professional organizations, activist coalitions, and other special interest groups: Marked improvements — or evidence that things were never as bad as once thought — are frequently viewed as existential crises, rather than welcome signs of progress.

Messaging Is Paramount

For Joseph, the narrative of a steeply escalating maternal mortality crisis never jibed with reality. “Obstetricians were upset when they kept hearing this business about things getting really bad,” he told me, “when they found they saw no change on the ground.” He also noted the pronounced anxiety pregnant women have suffered from hearing news reports claiming they were more likely to die in childbirth than their mothers’ generation had been. “Which is utterly untrue,” Joseph said.

In an interview, Christopher Zahn, ACOG’s interim CEO, allowed that there are active debates over preferred methodologies for measuring maternal mortality and that each method has its challenges. And he said his organization “would be jumping for joy” if the maternal mortality rate was, in fact, only a fraction of what was once thought. But due to what Zahn called flaws in the study team’s methodology, he argued the actual rate was higher than what the team claimed.

Furthermore, the paper’s findings, Zahn argued, were being misrepresented by the press, including in The Wall Street Journal, which ran an opinion piece declaring that the CDC had pushed a “phony ‘pregnancy crisis.’”

He was particularly concerned about the paper’s bold claim that, given maternal mortality comprises less than 2 percent of deaths in women of childbearing age, this “may warrant some reconsideration of public health priorities.”

The nation might begin considering this issue as “no big deal,” Zahn worried, “and we can just take the foot off the gas pedal.”

Messaging, Zahn asserted, was paramount.

Keeping the Public Hypervigilant

According to Deana Rohlinger, a professor of sociology at Florida State University, the vested interests of a group like ACOG bias them toward suspicion of countervailing evidence. “If you’re an interest group, you need people to give time, money, and various kinds of energy,” said Rohlinger, who is the author of “Abortion Politics, Mass Media, and Social Movements in America.” She said such groups have an intrinsic motivation to foment a permanent perception of threat and sense of anxiety about their area of concern.

“That’s what folks respond to,” Rohlinger said. “They say, ‘This is the issue that rises to the top of my agenda now, because maternal health is in danger or abortion rights are in danger.’”

Covid-19 offered society a crash course in the use of fear, by government and interest groups alike, as a tool to direct the public’s attention, control behavior, and marshal resources.

Tracy Beth Høeg, a physician epidemiologist at the M.I.T. Sloan School of Management, called ACOG’s response to the maternal-mortality study “sad and not surprising.”

“We saw the same thing with the American Academy of Pediatrics when they continued to make Covid a crisis in children to advocate for more funds to ‘safely’ reopen schools and repeatedly fear mongered about Covid in children,” Høeg wrote in an email.

In reference to interest groups overall, she added: “The people in these groups also want to believe what they are doing is making a critical difference.”

The Memory Hole

Remember the recovered memory movement? The leaders of that psychiatric maelstrom thought they were making a critical, and positive, difference.

Starting in the late 1970s, an ever-burgeoning population of adults, mostly women, became convinced they had suppressed memories of childhood sexual abuse. Mental health professionals fueled this socially contagious fervor, which tore apart families and captivated the media. By the 1990s, though, damning legal testimony in civil cases, along with emerging psychological research, began to reveal that most of these people were not victims of sexual abuse, but of unscrupulous psychotherapists.

Jena Martin, the producer of the riveting podcast, “The Memory Hole,” which chronicled the recovered memory craze, said that when presented with the hopeful assertion that their patients had likely not in fact been abused, recovered-memory therapists “were really quite instantly on the defensive.” Martin said it was worse for these counselors to challenge their foundational belief in the Freudian notion of repression than to celebrate the fact that their patients’ childhoods had not been marred by such trauma.

Not every such response by a special interest group to hopeful news is quite so cynical. Anti-crime and victim advocates, for example, often respond with similar resistance to reports of declining crime. But Janet L. Lauritsen, a distinguished professor emerita in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, cautioned against conceiving of such responses as a simple denial of reality. There is a chasm, Lauritsen said, between dispassionate data and advocates’ raw, hands-on experience of working with crime victims.

“They run on shoestring budgets,” Lauritsen said. “They run on volunteers. They make no money. And so, when they hear that the problem is 30 percent lower than it was five years ago, they don’t see it in their door.”

She also noted an age-old public-health catch-22: When workers in this field succeed in improving public health, they are the first ones to lose resources. She recalled victims’ advocates entreating her not to broadcast lower crime rates, saying, “You can’t say that or they’re going to start cutting our funding!”

With that threat in mind, the worst thing that could happen to an advocacy nonprofit is what befell the nation’s HIV organizations: The AIDS crisis ended.

During the 1980s, a vast network of what are known as AIDS service organizations, or ASOs, sprouted up nationwide to address the manifold needs of people with the disease. But then, in 1996, the approval of combination antiretroviral treatment transformed HIV into a manageable infection.

In tandem with declining public anxiety, private fundraising for AIDS service organizations cratered during the 2000s. Despite plenty of remaining need to fight HIV and provide services, the ASO network sustained waves of closures and mergers. Amid this downturn, many people in the HIV community never forgave journalist Andrew Sullivan — HIV positive himself — for signaling the end of the epidemic’s crisis phase in a triumphant, if world weary, 1996 New York Times Magazine article titled “When Plagues End.”

“I was vilified for this,” Sullivan said. “It was really vicious. I was treated horribly by people who had completely lost the plot.” That plot, of course, was to tame the AIDS scourge — and to educate the public about the dawning of this new, hopeful chapter in HIV history.

Suppressing information about improvements in public health, Sullivan added, “hurts everyone.”

Making the Best of Precious Resources

The greatest existential threat facing humanity is, at least arguably, climate change. Advocates in this space must expend enormous resources battling those who would deny it or dismiss it as a matter of concern. But even here, nuances in the data suggesting anything promising are far from celebrated.

Bjorn Lomborg, the president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, offered a chart in a 2021 Wall Street Journal essay that showed a steep reduction in climate-disaster-related deaths over the past century. “Human beings are pretty good at adapting to their environment, even if it’s changing,” he wrote, highlighting a cause for hope.

Republican lobbyist and climate change denying gadfly Steve Milloy insisted that major climate nonprofits have simply ignored this fact about human adaptation.

“I have never seen an environmental group say anything hopeful or point out anything that is contrary to their narratives,” he said.

However, critics rightly pointed out that Lomborg, whose positions on the threat posed by climate change have long antagonized mainstream activists and scientists, disingenuously started the chart in the 1920s, which saw a dramatic spike in climate-related deaths compared with the previous two decades. But this effort to debunk him nonetheless tended to overlook the fact that things have long improved on this measure.

Edward Maibach, a climate change communication expert at George Mason University, acknowledged that climate advocates such as himself tend to be overly fixated on the challenges ahead. “The trees and boulders that are blocking our progress toward the mountain top may look daunting,” he said in an email, “but let’s not lose sight of how far we have come up the mountain already.”

Whether that’s apt advice for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is a matter of opinion. But Rohlinger’s research about the sociology of movements suggests to her that keeping the public engaged does require maintaining a delicate balance between realistically fomenting concern and offering hope. Interest groups “have to create that space for optimism,” Rohlinger said, “because if it’s all dire all the time, then people become very apathetic.”

Indeed, why would anyone give time, money and energy to a hopeless cause, no matter how tragic? We must pick our battles.

What Joseph and his coauthors suggested in the passage of their maternal-mortality paper that so troubled the leaders at ACOG is that maintaining precise public-health surveillance and reporting of the problems society faces is vital, because this helps us properly allocate funding according to need and yield the greatest net benefit from finite resources.

“The range of threats to human health are tremendous and the information ecosystem we have tends to highlight one or a very small number of them,” said Jay Bhattacharya, a professor of health policy at Stanford. Referring to the new maternal mortality paper, he said that “studies like this that accurately measure risk, I think are a big boon.”

Thanks for a smart and thought provoking analysis!

I'd add that there are significant differences between a professional association like ACOG and advocacy groups for political and social causes. ACOG will always have a reason to exist as long as doctors continue to specialize in obstetrics and gynecology. They don't gin up meaningfully more business by throwing the organization's weight behind one or another viewpoint on the true rates of maternal mortality. Nearly all pregnant women in the U.S. avail themselves of ob/gyn services. In fact, siding with the highest estimates makes the profession appear potentially less competent unless they're willing to blame mothers themselves for bad outcomes. Indeed some doctors have blamed women, fingering obesity and birth beyond age 35 (for example); but they don't represent the profession as a whole.

Motives look somewhat different for advocacy groups that are organized around specific issues. You write of HIV/AIDS orgs, and I'm guessing you made a deliberate choice to leave transgender politics out of this piece. The pivot of HRC and other gay-rights orgs to trans issues post-Obergefell and Bostock is the most paradigmatic example I can think of, however, for organizations to continue to dwell on negatives and problems. Otherwise, there aren't major battles to be won anymore at the policy level, even though there are still pockets of cultural opposition to gay people and LGB equality.

In short, the dynamic is different depending on whether a group has a purpose beyond particular contentious issues.

Thank you for this great essay.

WRT pregnant women, there’s the added narrative about racism, that black women in the U.S. face even higher rates of maternal mortality than white woman.