Trump’s Assault On Aid for HIV Abroad

The Trump administration's freeze of all foreign aid has thrown a major program to prevent and treat HIV in poor nations into chaos and put millions of lives in jeopardy.

I remember how the pride glowed across the health minister’s face when she heralded the “great news from the Kingdom of Swaziland.”

It was July 2017, and I was in Paris to report on the biennial International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science. Having grown up gay under the shadow of AIDS, I’d gotten involved in HIV-related volunteer work in high school in the mid-1990s and proceeded to start my reporting career by covering the global pandemic. The optimism I witnessed at that conference was unparalleled since the approval of antiretroviral treatment in 1996 ended the crisis phase of the U.S. epidemic.

In a press conference announcing the Paris confab’s top research findings, we heard from Dr. Velephi Okello, a deputy health minister from Swaziland, which is a small nation nestled within South Africa’s borders. The country, since renamed Eswatini, was burdened with a superlatively severe HIV epidemic, with the highest proportion of its population living with the virus and the highest annual transmission rate of any nation.

And yet, in just five years, Dr. Okello reported, Swaziland had doubled, to 73 percent, the share of its HIV population receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral treatment and slashed its transmission rate in half.

“We are going to build upon these successes,” said Dr. Okello, beaming. “In the end, we would like to see a Swaziland that is free from AIDS.”

This vision of a post-plague era for sub-Saharan Africa, where about two-thirds of the globe’s 38 million people with HIV live, was made possible by the largesse and leadership of the United States. It was made possible because early in his administration, George W. Bush had been shaken by the suffering and despair visited upon the continent by this insidious virus. The expensive antiretroviral medications that had spurred a Lazarus effect among Americans with AIDS remained out of reach in poor nations.

And so, Mr. Bush charged Dr. Anthony Fauci, the longtime head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, to design a foreign aid program to fight HIV that would rival the Marshall Plan in its scope and ambition.

In his 2023 State of the Union address, Joe Biden gave his predecessor credit where it was due. Marking the 20thanniversary of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, he said thunderously: “It’s been a huge success!”

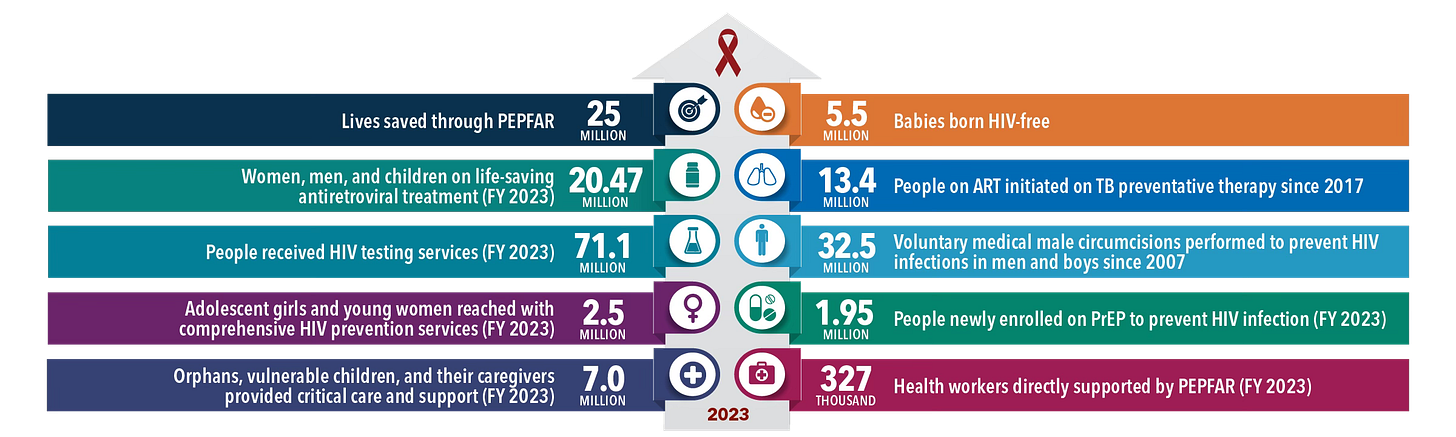

To date, PEPFAR, which operates in 58 countries but focuses the bulk of its efforts in 13 hard-hit sub-Saharan African nations, has channeled more than $100 billion into combatting HIV abroad. Since 2004, it has saved 25 million lives; and it currently provides life sustaining antiretroviral treatment to over 20 million people. Funded at about $6 billion annually since the Obama administration, PEPFAR is widely considered among the greatest foreign-aid public-health success stories in history.

But today, PEPFAR’s huge success is at risk of backsliding into calamity.

This perilous turning point for the global HIV fight comes thanks to the second Trump administration. With the stroke of his presidential pen this week, Donald Trump, newly replanted behind the Resolute Desk, signed an executive order that has “paused” all of the federal government’s $40 billion in foreign aid. This is pending a 90-day review to ensure the spending is in keeping with the administration’s “values.”

This has thrown PEPFAR into chaos.

True, Marco Rubio, freshly anointed as secretary of state, did provide a waiver on Tuesday that permitted foreign-aid programs to continue providing lifesaving medical treatment.

However, many of my sources working in the HIV field around the globe—most of whom made the unusual and remarkable request to speak anonymously for fear of reprisals from Trump’s administration—have told me that the waiver has done little to maintain the steady supply of antiretrovirals to people with the virus.

Not only was the waiver written too vaguely, it failed to provide clearance for the vast, complex infrastructure required to care for people with HIV. Staffers can’t enter clinics and offices when the rent is paid by PEPFAR. Nor can they use vehicles owned by organization. The program’s data system, which handles appointments and tracks the spread of the virus, has been taken offline.

Additionally, complementary HIV programs funded by USAID and the CDC’s international arm have been frozen. And Mr. Trump’s ambition to withdraw from the World Health Organization will only further compromise the multilateral cooperation that buttresses efforts to combat existing and future epidemics, such as from Marburg or mpox.

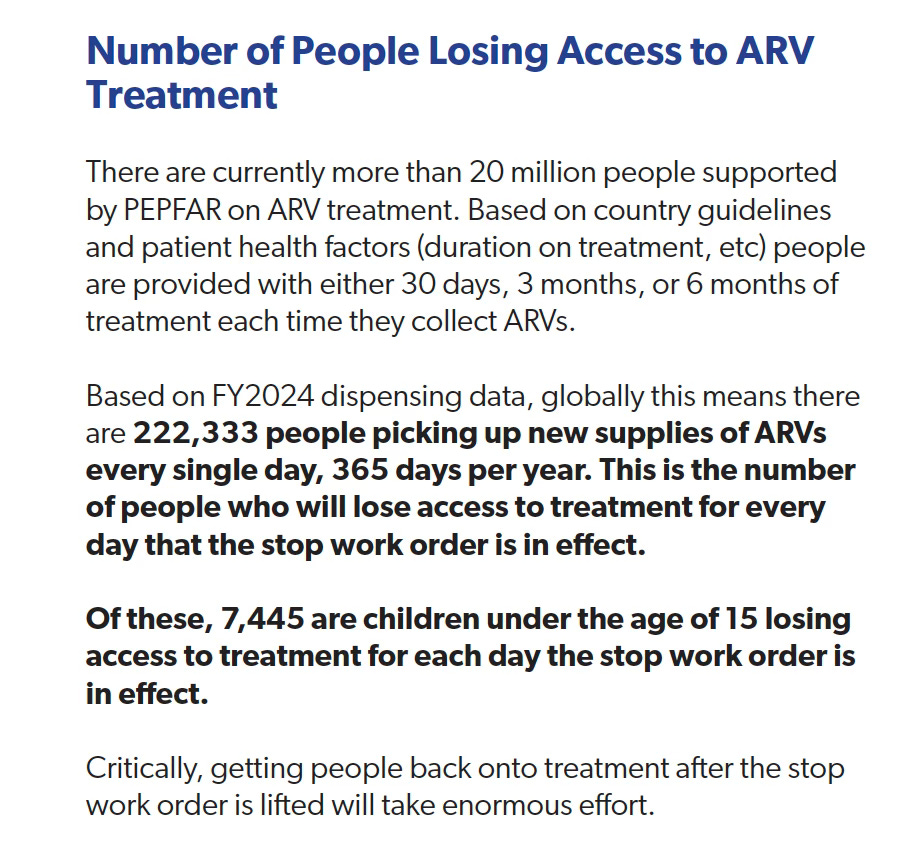

Policy experts at amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research estimate that 222,000 people pick up their HIV medications daily from PEPFAR-funded clinics and pharmacies. Within a few weeks of a treatment interruption, HIV rebounds and becomes transmissible—raising the risk of transmission within communities and from mother to child. If the 680,000 HIV-positive pregnant women cared for by PEPFAR cannot remain on antiretrovirals, amfAR estimates that within 90 days, 136,000 of their babies will be born with the lifelong infection.

Even if antiretrovirals remain at least partially available, the Trump administration’s actions will likely cause widespread damage abroad, my sources say. PEPFAR also supports a host of programs for HIV testing, prevention and surveillance, as well as efforts to support the futures of girls and to care for victims of intimate-partner violence. All of these programs are now frozen; their staffers have been furloughed.

In a statement posted Wednesday that rationalized its abrupt halt to foreign aid, the State Department ticked off examples of programs it said ran contrary to its values. It scoffed at paying for sex education for girls—a major and vital component of PEPFAR’s work, the lack of which will only lead to more HIV infections among this vulnerable group.

We know just how damaging interrupting HIV treatment is thanks in large part to research sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. To the apparent chagrin of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who if confirmed to run the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services promises an eight-year interruption to infectious disease research funded by the federal agency, the NIH has remained the global leader in HIV research since the dawn of the epidemic in the early 1980s.

The early generations of HIV drugs were profoundly toxic. So, during the early 2000s, the NIH funded a randomized clinical trial to see if “drug holidays” could yield a net health benefit. They did not. These breaks, the research showed, raised the risk of opportunistic disease and death. This finding revolutionized how HIV is treated and ultimately gave rise to another landmark NIH trial, which in 2015 proved that starting treatment soon after diagnosis was preferable to delaying.

Shutting down HIV testing programs abroad will, consequently, cause widespread harm by delaying people from starting treatment.

Going off HIV medications also poses a risk that the virus will develop resistance to those drugs. This can complicate future treatment options, both for the individual and anyone who contracts the virus from them.

NIH-funded research conducted during the 2010s further helped prove that successfully treating HIV eliminates the risk of transmitting the virus through sex—a scientific consensus that Dr. Fauci announced he supported at that 2017 conference in Paris. That finding, coupled with the research that supported treating immediately after diagnosis, drove a test-and-treat ethos that PEPFAR has run with and which has paid dividends in sub-Saharan Africa.

Evidence of antiretroviral treatment’s dual powers was on proud display at the 2017 conference in the mathematically elegant figures out of Swaziland, where PEPFAR was the engine driving that nation’s success in combatting HIV.

Dr. Debbie Birx, who directed PEPFAR at the time, was also on hand at the Paris conference. Dressed to the nines, she gave wonky presentations about how PEPFAR was using a data-driven approach to do more with less, spending American taxpayer dollars with ever-greater efficiency in the face of perpetual flat funding.

George W. Bush made explicit that his faith motivated him to launch PEPFAR. But today, the predominant brand of Christian conservative, with Vice President J.D. Vance as its talisman, will have none of this altruistic sentiment when the money to help others is channeled through the government and supports people who live far out of sight. The Heritage Foundation has spent many years attacking PEPFAR and fomenting opposition to the program in Congress.

“It is totally sociopathic,” one academic infectious disease experts told me, insisting on anonymity for fear of drawing the ire of the Trump administration. “The US has garnered so much favor with Africans in general, because we’re seen as really caring for people and their immediate health care. This sociopathy is quickly wrecking that trust and that goodwill. That’s devastating.”

Following his confirmation, Rubio spelled out his three-part litmus tests for foreign aid: “Does it make America safer? Does it make America stronger? Does it make America more prosperous?”

Where PEPFAR is concerned, the answer to all three questions appears to be “yes,” according to the experts I spoke to this week. Promoting goodwill toward Americans by saving African societies from collapse has reduced the threat of global conflict, making America safer and stronger. Secretary of State Colin Powell told Bush that this was a valuable source of “soft power” abroad.

Crippling or ending PEPFAR will compromise the United States’ standing and strategic interests in Africa. China, which has ramped up investment in the continent, is waiting in the wings to fill that influence void should our nation recede.

As for prosperity, PEPFAR facilitates invaluable HIV research that has been a boon for U.S. pharmaceutical companies, such as Gilead Sciences. Many of the clinical trials that have given us new biomedical methods of HIV prevention were conducted in Africa through PEPFAR’s infrastructure. Any hope for an HIV vaccine will pass through those same channels.

The Trump funding interruption is without precise historical precedent, but it evokes a macabre chapter in South Africa’s history. During the early 2000s, the nation’s then-president, Thabo Mbeki, fell prey to the influences of American HIV denialists and, as a result, delayed by several years the rollout of antiretrovirals in his nation. Researchers later estimated that this perverse exercise of power cost the nation 2.2 million cumulative years of life among 300,000 people who needlessly died of AIDS.

Regardless of what portions of PEPFAR are permitted to function for the next three months, the program is barreling toward a funding cliff. Congress has reauthorized the program for five-year cycles three times, always with bipartisan support. But now, quibbling by certain Republicans about PEPFAR having even the slightest or tangential connection to abortion services have politicized the program and put its very existence jeopardy. Its current, one-year reauthorization is set to expire on March 25, precisely when the current 90-day funding “pause” period ends.

Many of the sources I have spoken to this week have acknowledged that it is only reasonable to plan for PEPFAR to increasingly hand the reins of its operations to local governments. The program has indeed done so over time. But pulling U.S. involvement out overnight, my sources tell me, will only lead much of this productive and efficient system to collapse.

On Thursday, I spoke with Deo Mutambuka, executive secretary of the Rwanda Network of People Living With HIV/AIDS. He spoke ruefully of the chaos and confusion the Trump administration had caused PEPFAR workers and people with HIV across sub-Saharan Africa.

“It’s so scary,” he said. “It turns everything upside down.”

“We need to speak loud and see what can be changed,” he said.

I am an independent journalist, specializing in science and health care coverage. I contribute to The New York Times, The Guardian, NBC News and The New York Sun. I have also written for theWashington Post, The Atlantic and The Nation. Follow me on Twitter: @benryanwriter and Bluesky: @benryanwriter.bsky.social. Visit my website: benryan.net

What a disaster, thank you for reporting it so thoroughly!

I would like all Africans to have access to the education and medications that are necessary to prevent and treat HIV. I'm just not sure whether the best way to achieve that is for the US to pay for it. I worry that so many years of aid has set up a poor incentive structure for the individual countries to take responsibility for the health and well-being of their citizens. I'm concerned that long-distance funding discourages NGOs from doing their work as cost-effectively as possible. As you point out, this program has been in force for twenty years, and yet we're still paying rent on the buildings they use to run their clinics.

The entire African continent has a GDP of about three trillion, which is three thousand billion dollars. Per your article, the US expenditure on PEPFAR is six billion a year. It doesn't seem unreasonable to ask these countries to allocate 0.2% of their own spending to continue lifesaving services. By gifting this funding, we are also effectively relieving their governments of other budgetary items--items that we aren't aware of and may not even approve of. There are so many reasons it's better to teach a man to fish, rather than feed him a fish.

Perhaps phasing out the aid over Trump's four years would have been a more gradual way of nudging the programs in these countries toward other sources of funding, but that's different conversation.